Arnaldo Jardim

Congressman in the Federal House of Representatives

Op-AA-21

Clean and fair ethanol

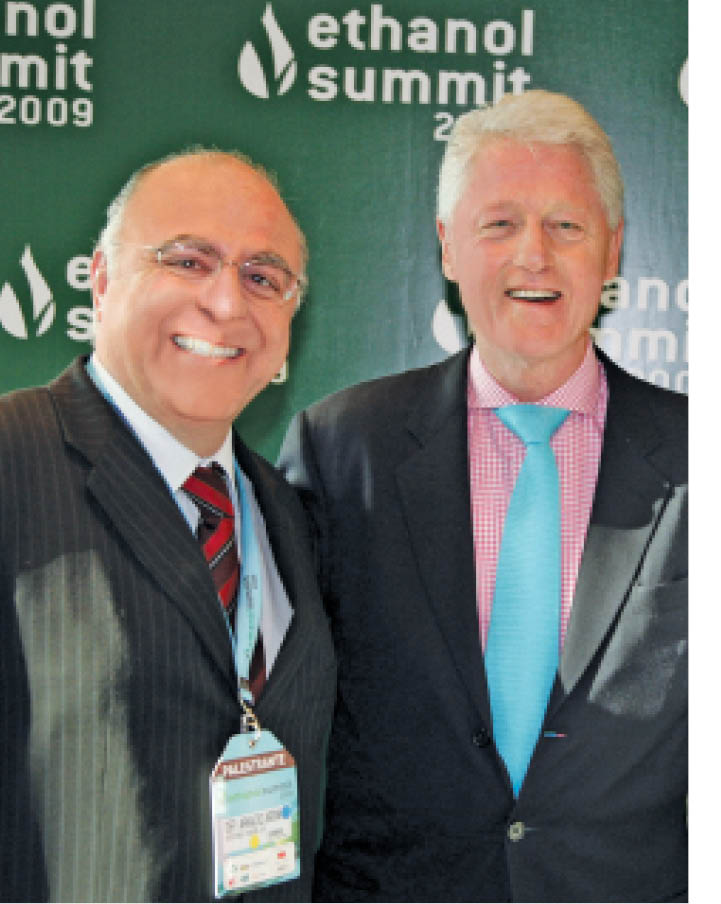

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton, during the 2009 Ethanol Summit, well summarized the challenge of the national sugar-based energy industry: it does not suffice to demonstrate that we are more efficient, we must incorporate the principle of sustainability into our entire production chain. Only in this manner will we be able to open the world’s main markets for our ethanol, tearing down non-tariff barriers. Predominantly, two issues stand out: labor conditions and the risk of deforestation to expand production.

Obviously, there are other obstacles to creating a global biofuel market, such as the standardization of ethanol and its consequent transformation to become an environmental commodity, as well as the dissemination of ethanol production to more countries, mainly emerging ones that already produce sugar from cane, through the transference of technology and know-how.

Notwithstanding the solid fundaments and the huge potential of agro energy as a clean and renewable energy alternative, we still are faced with the propagation of myths, untruthfulnesses, or simply disinformation, which convey a reality that does not correspond to the industry’s state-of-the-art. The challenge now lies in showing the world that our ethanol is sustainable.

Social responsibility: In June we experienced a historical moment for the industry: the signing of a national commitment to improve labor conditions in the sugar and alcohol industry, involving public authorities, the productive sector and the workers. In what is a voluntary adhesion, mills and distilleries that commit to implementing improvements will be listed on a sort of “white list” of good practices.

The agreement was coordinated by the General Secretariat Office of the Office of the Presidency, with support from CONTAG (National Confederation of Workers in Agriculture), FERAESP (Federation of Salaried Rural Workers in the State of São Paulo), the National Sugar-based Energy Forum and UNICA (Sugarcane Industry Association).

It will benefit some 800,000 harvest workers and among the benefits one should highlight:

• Direct hiring and registered employment;

• Measuring of production in the presence of worker representatives (with a previously agreed upon price per ton of harvested sugarcane);

• Free-of-charge supply of individual protection equipment and two daily collective breaks;

• Alphabetization and improvement of worker education, in addition to promoting professional qualification;

• Companies will provide thermal containers for preserving the food temperature;

• Union members will have access to the work sites;

• Transportation will be free-of-charge and safe.

″RenovAction″: This initiative is in tune with a program announced by UNICA, responsible for more than 60% of the national production of sugar and ethanol, during the 2009 Ethanol Summit, called ″RenovAção″ – Sugarcane Worker Requalification Program. In the State of São Paulo, the largest national sugarcane producer, there is a law, of which I am the author, that organized the procedures to put an end to the incineration practice by 2021, but environmental issues and increasing technological innovation made possible an agreement in 2007, to anticipate the end of incineration to 2014.

Thus, manual labor is gradually being replaced by mechanized planting and harvesting processes. Alert to this, industry companies are already developing isolated initiatives to absorb this labor following requalification, warranting better job opportunities within their own mills, or in segments of the production chain, for some five thousand people.

Thus, manual labor is gradually being replaced by mechanized planting and harvesting processes. Alert to this, industry companies are already developing isolated initiatives to absorb this labor following requalification, warranting better job opportunities within their own mills, or in segments of the production chain, for some five thousand people.

With the intent of expanding this kind of service to seven thousand workers per year, UNICA, FERAESP, companies of the production chain – Syngenta, John Deere and Case IH, with support from the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB), came together to launch an ambitious requalification program, which will serve six production regions in the State of São Paulo.

The courses offered the industry include: sugarcane plantation driver, picking machine operator, picking machine electrician, truck electrician, picking machine mechanic, truck mechanic, tractor mechanic, tractor electrician, and welder. Other professional areas are: apiculture and reforestation, horticulture, handicrafts, computer science, sewing, civil construction, the hospitality sector and tourism.

Growing without deforesting: At the 2009 Ethanol Summit I moderated the panel Biofuel: Growing without Deforesting, in which the speakers were: Senator Kátia Abreu, President of CNA – National Confederation of Agriculture, Senator Marconi Perillo and Federal Congressmen Mendes Thame and Marcos Montes. The national ethanol production is breaking successive productivity records, while at the same time Brazil is consolidating and gaining space in the global food market, making analysts predict that soon we will become the “cellar of the world”.

This reality has only been made possible thanks to investments in technology and innovation, which allowed us to produce more on each arable hectare, in a sustainable manner, seeking in efficiency an alternative to overcome the obstacles of the so-called “Brazil Cost”. However, we are still in need of a concrete agro ecological zoning law for sugarcane, a measure advocated by the Federal Government, but which has as yet not made it off paper. All participants in the debate showed their commitment to approving this measure in the National Congress to preserve Amazonia and the Pantanal.

In this respect, there are two fundamental aspects. First, there is a proposal that is being designed without a clear target as to when or in how much time it would be put into practice, and there still is no definition for said policy’s implementation strategy. This zoning is important for several reasons. The foremost is to signal the Brazilian commitment to foster sugarcane production expansion without increasing deforestation, both in Amazonia and in the Pantanal. To us Brazilians, this seems obvious, but it is not to foreigners. Another positive aspect would be to pave the way to creating zoning in other agricultural and livestock breeding sectors currently in the spotlight, such as beef cattle. With that, we would indirectly be fostering the intensification of grazing land use.

Research and development: In Brazil, of the 340 million hectares of arable land, only 90 million are supposedly appropriate for growing sugarcane, which currently occupies 7 million hectares (of which half are used to produce sugar). Nowadays all products occupy 62 million hectares. Thus, only 5% of the agricultural land is destined to producing ethanol, on which more than 24 billion liters/year are produced. To have an idea of the growth potential, let us do a simple calculation.

There are 200 million hectares of grazing land, of which 90 million are suited for agriculture (of these, 22 million are suited for planting sugarcane). Thus, one estimates that the country can expand its sugarcane plantation area for producing ethanol by up to seven times. Agronomic research on sugarcane shows that, if in 10 years the productivity of ethanol per hectare were to double, we would produce another 20 billion liters of ethanol in the same area currently used, reaching a limit of 280 to 300 billion liters of ethanol per year.

This, considering only non-irrigated land – unlike competing countries that need irrigation and hence, bear an additional cost to produce. Nobody questions the excellent prospects for our ethanol. After all, we have the best geographic, climatic, cultural, economic and technological conditions. Therefore, Brazil’s role can be – and will be – extraordinary, and we are preparing for that. However, in order for market expectations to be confirmed, companies, governments and the productive sector need to be alert to new requirements of a market being formed: efficient commercialization, respect for social and environmental norms and permanent investments in research and development.