Roberto Rodrigues

Coordinator of the Agribusiness Center of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV)

Op-AA-21

Biofuels in the global context

The world is dedicated to studies and research for the purpose of finding renewable, non-polluting energy that reduces global warming. Agro energy is ready to meet this demand, whether by producing biofuel, through bioelectricity, or by using pellets made of bagasse or dry leaves to replace mineral and vegetable coal in fireplaces of the cold countries.

Everything is ready: the agricultural technology, the industrial and the automotive technologies; we know how to do the mixing and the distribution; we know all about selling and we have erred so often that we could even only teach how to do things right. The existing global opposition to this alternative is really impressive.

Obviously one does not intend agro energy to be the only solution for the overriding issue of energy safety. However, there is no doubt that it is one of the good solutions that has already been resolved: there is nothing needing to be reinvented in order for it to become a globalized alternative. Even more than that: agro energy will certainly change the world’s agricultural paradigm positively, by defining the appropriate raw materials for producing energy, without competing against food.

Furthermore, it might change global geopolitics in a remarkable manner, providing the planet’s poorer countries opportunity for sustainable development. To produce agro energy is different from producing food, which any country can produce, albeit possibly at a high cost. Food safety unleashed the process of agricultural protectionism, which to this day limits negotiations to free up the market, but brought forth a solution for Europe’s supply problem after the war.

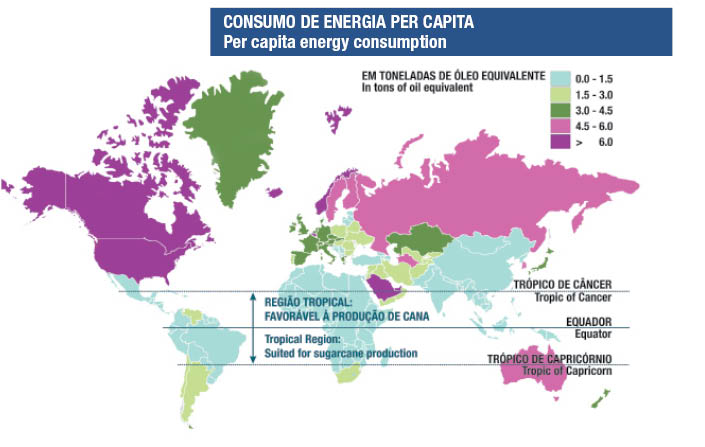

With subsidies, one can produce food anywhere, with artificialisms, like in greenhouses. But not agro energy, because it depends on 3 factors: soil (with everything in it, like nutrients and water), the plant, and the sun. Without abundant sunlight, there is no agro energy. Sunlight is available between the two tropics (Cancer and Capricorn), the region that encompasses the poor countries of Latin America, Africa and Asia.

These are the countries that will guarantee energy safety and will be financed by the big investors of the northern hemisphere.

These are the countries that will guarantee energy safety and will be financed by the big investors of the northern hemisphere.

With sugarcane or pulp, these countries will offer jobs and provide income and wealth, they will produce energy for their own consumption, which will foster their development, in addition to ex-portable surpluses, and they will furthermore produce food in rotation with sugarcane, as has been common practice in Brazil for decades, ever since the famous program “Sugarcane and Food”, implemented by Planalsucar in the seventies.

However, this will only occur following an internationally designed strategy, and what is lacking is the designer. There is the lack of the will to design.

The agreement between Brazil and the United States to produce ethanol in the Caribbean and in Central America is progressing, supported by Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Relations (Itamaraty), Export Promotion Agency (APEX), and the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB).

Preliminary talks in this matter have taken place between Itamaraty and the European Union to develop projects in Africa, and also negotiations between Petrobras and Mitsui are evolving with an eye on the Japanese and Asian markets. Hence, there is a logical pattern that irreversibly places biofuel within the global context. This is bound to occur, even if brought about by the typical inertia of big changes.

One could accelerate this project if Brazil had a clear strategy. However, unfortunately, we do not. Although the national discourse, both public and private, is perfect, actions are inconsistent, lacking direction, without planning and without a strategy. Obviously, efforts in the direction of planning are made, foremostly by the private sector, but they are held up by the lack of coordination of initiatives by the public sector.

Some 12 different ministries handle agro energy, not to mention Petrobras, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), the Brazilian Agriculture and Livestock Breeding Research Company (EMBRAPA), the National Metrology Institute (INMETRO), the National Meteorology Institute (INMET), the National Waters Agency (ANA) and dozens of federal, state, regional and municipal institutions.

All of these are staffed with top quality personnel, competent technicians, dedicated patriots awash in good will and good intentions... but who do not communicate among each other. That is why we do not move forward at a quicker pace. Hence, too, the cycles of high and low prices that make no sense. We do not even know for sure how much ethanol we need and/or want to produce over time, or which will be the production model, whether a wealth concentration or distribution one, as was proposed by Barbosa Lima Sobrinho in the Sugarcane Plantation Statute.

Interest groups debate the logistics, from production areas to consumer centers and ports. At least 3 groups are eager to build the ethanol pipeline, but there is room for only one. No decision is made as to who will handle storage, a fundamental theme for a strategic product such as fuel, which brought about co-generation.

Resources for technology are widespread, with no coordination among the excellent existing research centers, both the old and the newly created ones. The agricultural-economical-ecological macro zoning for sugarcane is ready, but it must be detailed by region, because this is what will determine the appropriate amount of credit for production.

Resources for technology are widespread, with no coordination among the excellent existing research centers, both the old and the newly created ones. The agricultural-economical-ecological macro zoning for sugarcane is ready, but it must be detailed by region, because this is what will determine the appropriate amount of credit for production.

Training human resources for a project of this magnitude is essential and is also being done without any coordination. The creation of models to publicize the technology abroad, which will allow us to sell entire industrial plants, complete experimental stations, production, mixing and distribution systems, is essential.

We should sell ethanol to the entire world, but first we must teach countries how to produce it, for them to create their domestic market. This is the only way to have a global market. Brazil stands to earn a lot of money selling the best it has, which is experience, its know-how.

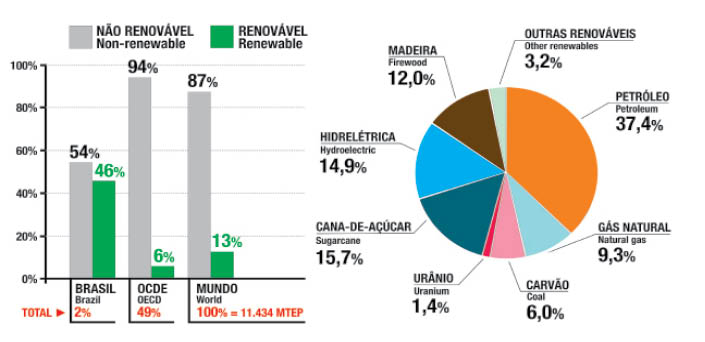

We must, therefore, handle all this and bringing about the implementation of the coordination could only be consistently achieved through a National Agro Energy Office, at the ministerial level, to put together this entire strategy, including communications. We need to show the whole world what a large number of people already know about our energy matrix, with its 45.8% of renewable energy. We must advertise the impressive reduction in CO2 emissions brought about by ethanol, in comparison with gasoline.

Balance of CO2 emissions: Considering the entire cycle, the production and consumption of 1,000 liters of ethanol emit 2,961 kg of CO2 in the plantation and harvest phases, 3,604 kg in the sugarcane processing, 50 kg in the transportation from the fields to the mill and 1,520 kg in the combustion in vehicles, totaling, throughout the process, 8,135 kg of CO2.

On the other hand, in growing the sugarcane necessary for the production of these 1,000 liters of alcohol, the photosynthesis process absorbs 7,650 kg of CO2 and the bioelectricity generated avoids the emission of 225 kg, totaling 7,875 kg of CO2, resulting, in a final balance, in the emission of only 260 kg of CO2, 89% less than gasoline, which would generate, at the end of the process, 2,280 kg of CO2.

We furthermore need to do away with these stupid myths that adversely affect the entire process, including two that nowadays are unbelievable: • that biofuel increases the cost of food; • that we are going to deforest the Amazon forest to produce ethanol. These are absurd myths, which have been extensively and thoroughly refuted, so that only ill will and bad faith still justify their existence. In short, biofuel will eventually be found around the world, because it is ready for that and necessary. However, this process would be faster if Brazil had an internal policy as powerful as the idea itself, which would ultimately more rapidly contaminate the whole world, for the benefit of all humanity.