Weber Antônio Neves do Amaral

Professor of the Luiz de Queiroz Higher School of Agriculture – USP

Op-AA-21

Opportunities for the production of food and bioenergy and the complementarity of sugarcane production chains and planted forest

We nowadays acknowledge that the world’s energy consumption is based on an unsecure, costly and environmentally unsustainable matrix, particularly due to the use of fossil fuels that further enhance the problems caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Although there is consensus concerning these problems and their medium and long term implications, the production and use of biofuel, an alternative to fuel derived from petroleum, and obtained from different biomasses, has been heavily criticized with respect to its competing with the production of food, and because it causes direct and indirect changes to the use of soil, for instance.

Brazil is in a privileged situation in this scenario, since the production of ethanol from sugarcane has served as a model for the production of biofuel in other parts of the world, while at the same time having broken successive food production records, obviously in addition to the fact that our energy matrix comprises 40% of renewable sources.

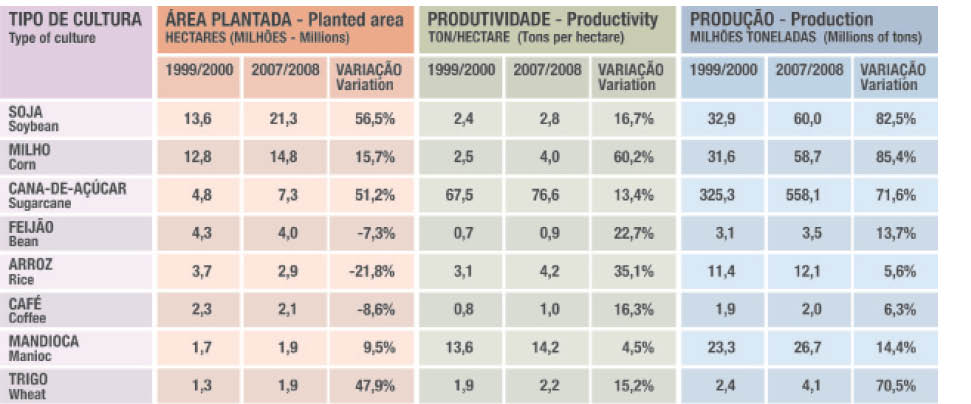

In the past ten years, the average productivity of the main agricultures in Brazil grew approximately 23%, whereas for corn and beans one noted increases of, respectively, 60% and 35%. The production of these same cultures grew approximately 40% in the same period. These numbers reflect expressive increases, both in terms of productivity and production.

This data has reinforced the country’s leading position in the world in the production of food, while at the same time reconciling, in a sustainable manner, the production and expansion of sugarcane, which, in the same period, showed productivity gains of approximately 14% and production increases of 70%. Years of investment in research, technological development and innovation were necessary in agricultural and industrial production activities, which allowed these uncommon productivity leaps among the largest food and bioenergy producers in the world.

Apart from serving as a model to reconcile the production of food with that of bioenergy, Brazil still has excellent competitive advantages to build a technological bridge to newer and cleaner energy sources and, additionally, to contribute to the production of food for the world.

Apart from serving as a model to reconcile the production of food with that of bioenergy, Brazil still has excellent competitive advantages to build a technological bridge to newer and cleaner energy sources and, additionally, to contribute to the production of food for the world.

Models for the integration of the production of food, sugarcane and planted forests already adopted in some regions of Brazil can be improved even more and expanded, taking into consideration that, in the case of sugarcane and planted forests, there are many similarities that can more easily be explained because:

a. these chains can complement the exploitation of the Brazilian potential of soil and climate;

b. they are greatly feasible with respect to obtaining credits associated with carbon markets;

c. the development of activities related to the production of inputs, equipment and technology for their production has the same reference base, strongly associated with agrarian and forest sciences;

d. for its production, sugarcane tends to occupy flat areas, whereas timber production is perfectly adaptable to other kinds of terrain;

e. in the case of sugarcane, the main focus is on transportation, at a time when ethanol stands out as its most important energy derivative, and furthermore, in combination with the huge energy potential represented by its residual solid biomass - bagasse. In the case of wood forests, their main energy utilizations aim at meeting industrial energy demand, with emphasis on steel production, in which it is used in the form of charcoal. Another important form of energy demand is wood used as a source of heat, for drying and processing agricultural produce and, lastly, for meeting the demand of millions of people who use it for cooking food, and

f. there are many similarities in terms of the tradition, use and technological options to obtain energy products from sugarcane and wood, including hydrolysis, fermentation, pyrolysis, gasification, combustion, and liquefaction processes, among others.

We are absolutely convinced that if these complementarities are adequately explored, these chains can positively influence a common strategic bioenergy policy for Brazil, which, if adequately planned, would not impact the continued sustainable production of food for our country, and one could continue to meet worldwide demand for protein, food and energy.