Luís Ricardo Bérgamo

Coordenador do Centro de Operações Agrícolas da Clealco

OpAA73

Gestão de operações e processos agrícolas

Antes do surgimento das atuais tecnologias de monitoramento e automação de processos agrícolas, a gestão das máquinas no campo era realizada basicamente via rádio de comunicação. As informações que chegavam aos analistas e gestores eram atrasadas, e a tomada de decisão era relativamente tardia em relação às atividades e aos fatos ocorridos, sem contar que tais informações, muitas vezes, não eram confiáveis e preenchidas de forma manual. Com isso, os problemas eram analisados e tratados tardiamente, com poucos reflexos positivos no curto prazo das operações.

A instalação de computadores de bordo nas máquinas agrícolas permitiu a obtenção de dados relacionados à telemetria (registros de sinais vitais do equipamento), principalmente com dados obtidos através da leitura da Rede CAN (Controller Area Network) e aos apontamentos das operações pelo operador, gerando em tempo real uma grande quantidade de dados das operações agrícolas.

Com os computadores de bordo on-line, inicia-se a análise dos dados de monitoramento e apontamentos para a gestão e tomadas de decisões. De nada adianta comunicação em tempo real se não há análise de dados e tomada de decisão na busca pela melhoria contínua dos processos e operações agrícolas.

Centros de Operações Agrícolas: Para apoiar as análises e as tomadas de decisões, os centros de operações – COA, ganharam destaque nas usinas, recebendo e analisando dados e transformando-os em informações, possibilitando uma visão holística de cada operação e comunicando a todo momento com os gestores, corrigindo os desvios operacionais em tempo real, evitando, assim, a ociosidade no campo e melhorando o sincronismo das operações. Com a missão de apoiar e auditar as operações, o COA deve sempre buscar a padronização das operações, e isso só é possível com disciplina operacional e alinhamento com o campo. A comunicação do COA com as equipes de campo é o ponto principal. Além de monitorar e passar informações relevantes aos líderes e gestores de campo, o COA deve apoiá-los na elaboração de planos de ação para a correção dos desvios identificados em cada parte do processo.

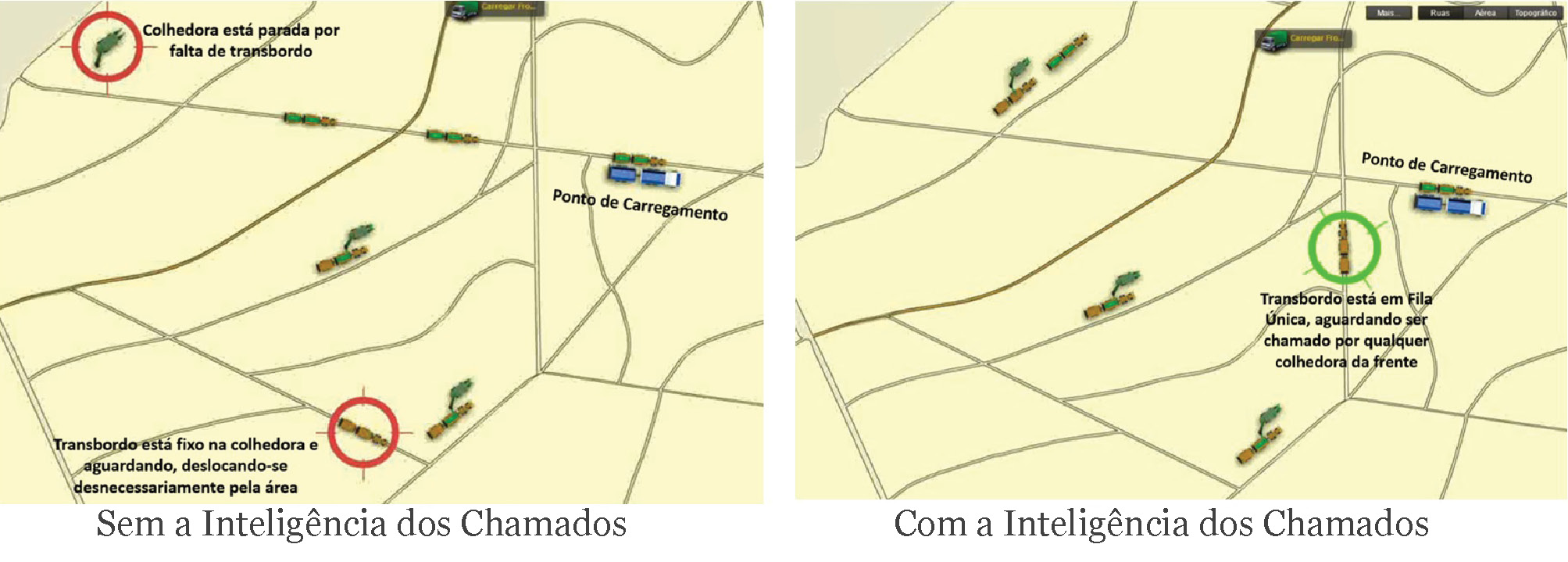

Exemplo de gestão na colheita com inteligência artificial: Um dos principais motivos de paradas de colhedoras de cana-de-açúcar é a falta de transbordo. Essas paradas não necessariamente apontam um mau dimensionamento da relação transbordo e colhedora, mas sim a falta de sincronismo das operações envolvendo esses equipamentos. Apenas como referência de valores, aproximadamente 14,2% das 24 horas do dia são perdidas em função da falta de transbordo (média de dados de 142 usinas coletados em julho/2022), o que representa 3,41 horas/dia/colhedora. Uma frente de colheita com 4 colhedoras perde 13,64 horas/dia, resultando em 200 dias efetivos de safra a grandeza de 2.728 horas perdidas. Não há dúvidas de que a automação desse processo reduz significativamente esse tempo perdido, transformando-o em produtivo e aumentando a eficiência operacional de toda a frente de colheita.

Há soluções tecnológicas com inteligência artificial embarcada com tomada de decisão autônoma e independente do operador, tendo como principal objetivo o aumento da eficiência operacional das colhedoras de cana, através do chamado automático dos transbordos pela colhedora, sem nenhuma intervenção do operador. A lógica dos chamados automáticos dos transbordos pelas colhedoras dar-se-á pelos tempos de cada operação, estando esses tempos sempre atualizados pelos últimos ciclos.

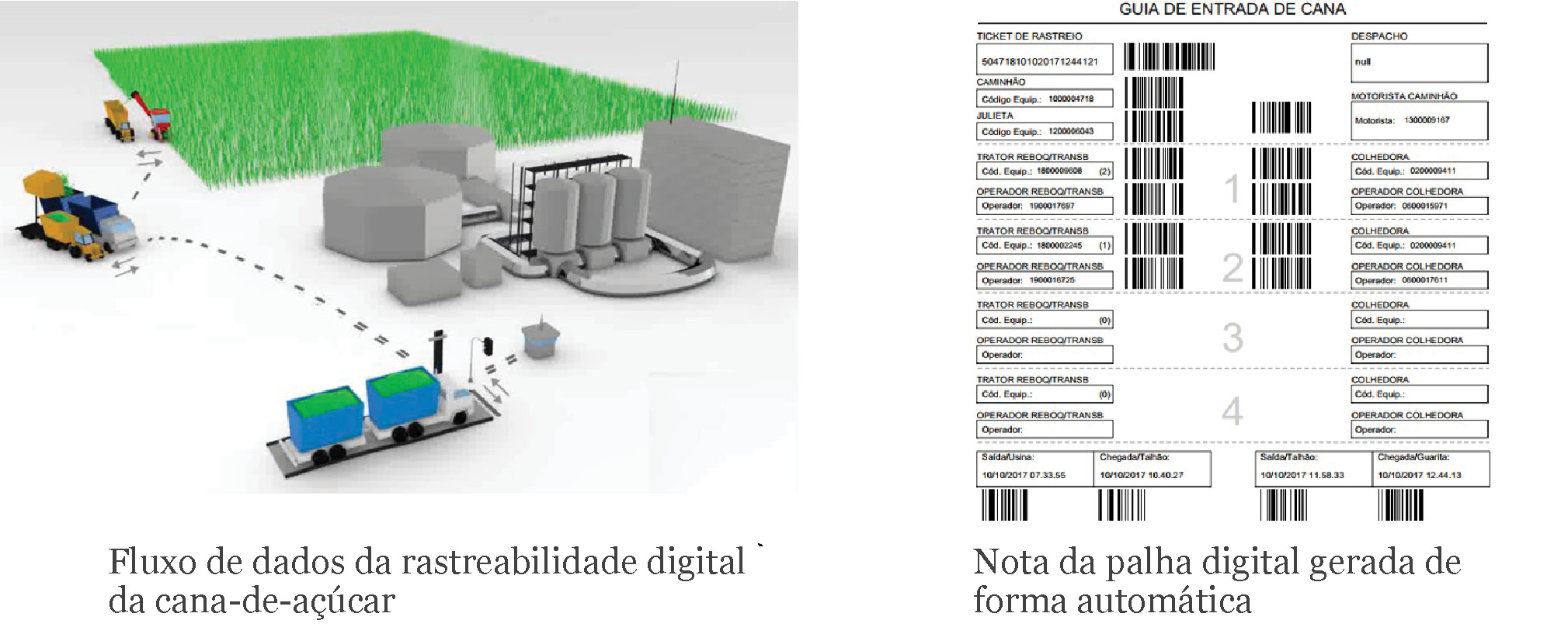

A rastreabilidade da cana é outro ponto que merece total atenção por parte das usinas. Notas de palha preenchidas de forma manual são passíveis de erros e podem gerar problemas complexos, como no pagamento de fornecedores de cana, prestadores de serviços, parceiros agrícolas, produtividade do canavial e produtividade de máquinas e equipamentos. Algumas tecnologias atuais rastreiam, de forma digital, todo o processo de CTT, desde o início da colheita até a balança de entrada, integrando todos esses dados com o ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) no momento da pesagem do caminhão. Dados como talhões, zonas, fazendas, colhedoras, transbordos, caminhões, carretas, operadores e motoristas são trazidos da lavoura de forma totalmente automática, garantindo a confiabilidade de todos eles.

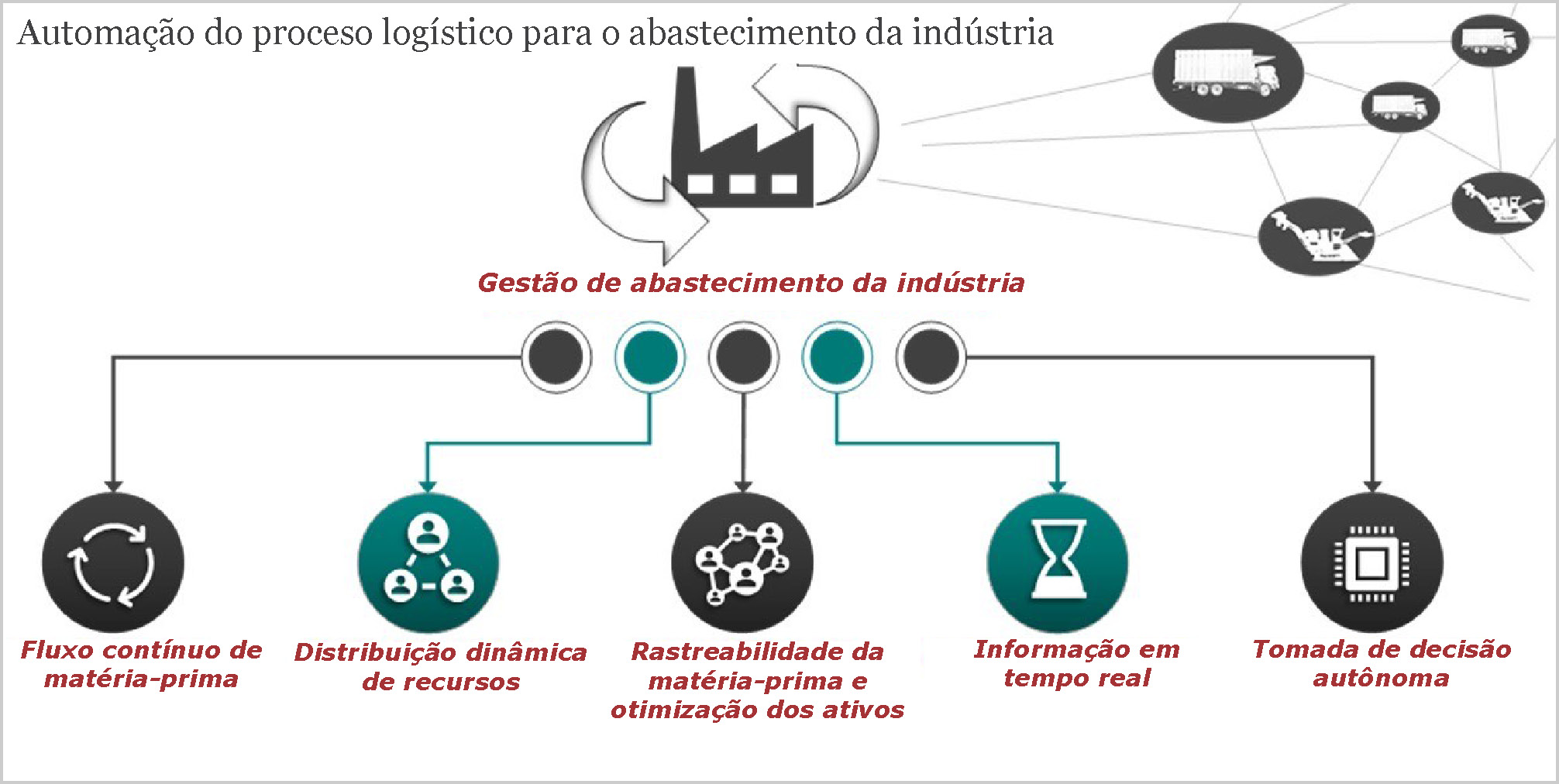

Com relação à automação da logística, tudo começa com o monitoramento on-line de todos os equipamentos envolvidos no CTT. Esses dados de monitoramento alimentam o sistema de logística em tempo real, ativando ou desativando os equipamentos em função do seu estado operacional do momento (trabalhando ou parado). Além dos dados de monitoramento, os dados dos ciclos dos transbordos são fundamentais na assertividade da logística, pois, com os tempos de todos os ciclos integrados a todas as colhedoras e com os eventos de paradas atualizados de forma on-line de todos os equipamentos, o cálculo da produção horária (t/h) de cada frente, considerando as capacidades de colhedora e transbordo, é atualizado minuto a minuto, possibilitando a integração on-line com o sistema de logística, garantindo assertividade no despacho de caminhões às frentes de colheita e otimizando a estrutura de transporte de cana. A falta de caminhão representa aproximadamente 2horas/dia dos apontamentos dos transbordos (média de dados de 142 usinas coletados em julho/2022).

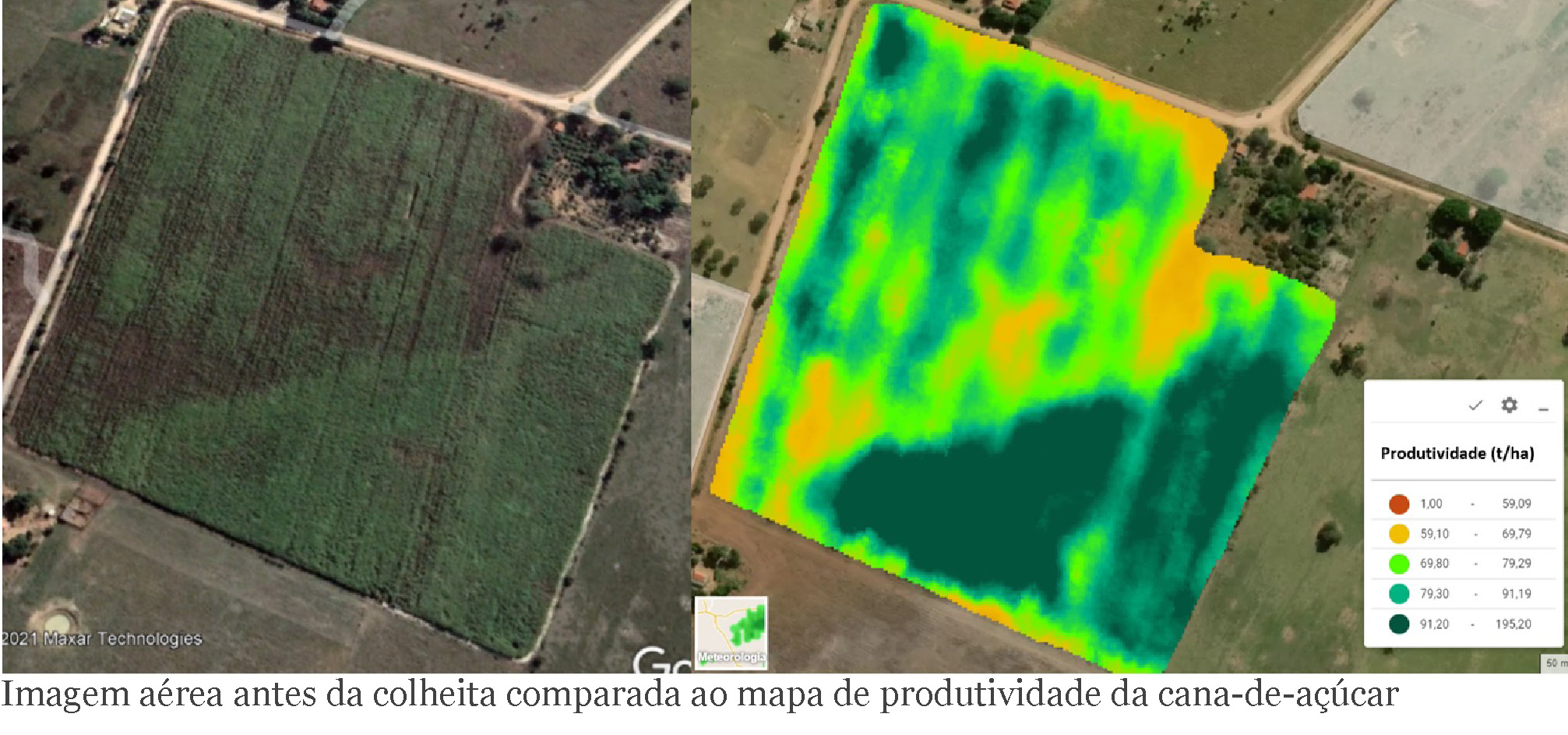

Existem, atualmente, tecnologias embarcadas em colhedoras que permitem a obtenção de mapas de produtividade do canavial de forma automática (sem nenhuma intervenção manual) e sem a utilização de sensores externos à máquina, evidenciando pontos de maior e menor produtividade dos talhões. Esses mapas podem ser utilizados para a aplicação de insumos e fertilizantes em taxa variável, buscando a otimização desses recursos, aplicando-os de acordo com a exportação de nutrientes da cana-de-açúcar e dos teores no solo.

Gestão englobando todas as operações mecanizadas: As operações envolvendo os processos de preparo de solo, plantio e tratos culturais também devem ser monitoradas e analisadas em tempo real, sempre atentando-se à maximização das horas produtivas dos equipamentos, incluindo os indicadores qualitativos de cada operação, como a velocidade e as sobreposições de operações e produtos, evitando retrabalhos e custos desnecessários.

Independentemente de quais tecnologias a serem adotadas pelas usinas, vale sempre lembrar que é de extrema importância o conhecimento prévio de cada uma por parte dos gestores, principalmente com relação às premissas que devem ser atendidas para que cada solução entregue o máximo de ganho aos processos e operações agrícolas. A falta de entendimento das funcionalidades dessas tecnologias pode impactar sua implantação, gerando retrabalhos e custos extras, além de retardar os retornos financeiros esperados para cada projeto.