Vinicius Bof Bufon

Pesquisador da Embrapa Meio Ambiente

OpAA76

Cana irrigada: ápice de excelência do manejo agrícola

A agricultura irrigada é a ferramenta mais importante para garantir excelência do manejo agrícola no setor sucroenergético. Dentre as culturas com maior peso na economia brasileira, a cana foi uma das últimas a investir no desenvolvimento e adoção da produção irrigada, apesar das décadas de uso de equipamentos para dar destinação à vinhaça e à água residuária. A exceção fica com algumas regiões do Nordeste.

Em tempos de agricultura 4.0 e de valorização de temas ambientais, a produção irrigada é o fator determinante para um agronegócio moderno a fim de otimizar recursos de todas as ordens e garantir produtividade com sustentabilidade exigida pelo momento histórico.

A irrigação surgiu há cerca de 6 mil anos, na Mesopotâmia. Foi por meio dela que houve uma transformação do uso da terra e da sociedade como nenhuma outra atividade já havia feito. Depois de milênios, busca-se hoje, através da irrigação, uma produção confiável de alimentos e energia limpa. Por isso, a irrigação talvez seja a mais importante e benéfica intervenção promovida intencionalmente pelo homem sobre seu ambiente.

No mundo desenvolvido, nas altas cúpulas de discussão sobre segurança alimentar e sobre sustentabilidade, a intensificação da produção por meio da irrigação é considerada a estratégia mais adequada para aumentar a produção mundial de alimentos e a energia limpa de forma sustentável.

No contexto das mudanças climáticas, com aumento da frequência e intensidade das secas nas principais regiões produtoras, associado à rápida migração da produção de cana para o Cerrado, é a irrigação que garantirá amortecimento das abruptas flutuações da moagem das usinas. Ela, também, reduzirá a forte queda da produtividade do início para o final da safra e diluirá os crescentes custos de capital e custeio por tonelada de cana e açúcar, por litro de etanol, por joule de energia, por metro cúbico de biogás, entre outros benefícios.

Essas flutuações abruptas de moagem, além de elevar substancialmente o custo industrial e agrícola de cada tonelada de cana, trazem transtornos quase incontornáveis à gestão financeira de maquinário e de equipe. Por exemplo, após um ano mais seco, a demanda da reforma de reforma do canavial pode passar de 15-17% para 25-30%. Com essa visão de seguro para sustentabilidade do negócio, muitas usinas têm acelerado substancialmente o investimento em sistema irrigado para uma fração de suas áreas.

O Mito da cana rústica:

Apesar de a irrigação ser considerada por lideranças mundiais e usinas de vanguarda tecnológica como uma das principais estratégias para garantir sustentabilidade ambiental à segurança alimentar e à produção de energia renovável, ainda existe acentuada desinformação.

Um exemplo é o mito de que a cana-de-açúcar é uma planta rústica e, por isso, não precisa de muita água ou de irrigação. Inclusive, esse argumento também já foi utilizado de forma recorrente no início da produção irrigada de diversas culturas que hoje fazem amplo uso da irrigação no País, como o café, laranja e alguns grãos.

Talvez, se compararmos a cana com algumas outras culturas, podemos dizer que essa afirmação é verdadeira, já que a cana precisa de menos água para sobreviver. Contudo, no contexto da produção comercial, o objetivo não é a mera sobrevivência da planta. Ao contrário, num sistema de produção sustentável, ofertam-se as melhores condições para que a cultura expresse seu potencial genético e produza com eficiência. Por isso, não basta que a cana sobreviva.

No passado, a cana era produzida somente no litoral e no bioma Mata Atlântica, e, de fato, em um ambiente de oferta hídrica mais bem distribuída ao longo do ano. Mas, mesmo assim, com certa frequência anos mais secos traziam fortes impactos negativos à produção.

Com o passar dos anos, e por diversas razões técnicas, logísticas, econômicas e sociais, as lavouras migraram para o bioma Cerrado, principalmente em São Paulo, e mais tarde para Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Goiás, Tocantins e, finalmente, o Pará.

Hoje, mais de 50% da cana-de-açúcar do País é produzida no Cerrado, cujo período de seca pode se estender por 4 a 7 meses. Nesse ambiente, não somente o desenvolvimento da planta é tremendamente reduzido, mas também a brotação e a longevidade das soqueiras.

Seguindo a lógica da Lei dos Mínimos de Liebig, o fator de produção mais restritivo pode não ser a água em um contexto de baixíssimo aprimoramento tecnológico e de gestão.

Mas, atualmente, o setor evidencia grandes avanços no manejo varietal de fertilidade, de ervas-daninhas, de fitossanitário, sem mencionar a grande mudança da colheita manual de cana queimada para colheita mecanizada de cana crua, e tantos outros aprimoramentos tecnológicos e gerenciais. Ainda assim, por restrições hídricas, não se tem conseguido há décadas uma evolução significativa de produtividade.

Portanto, a água, que sempre foi o principal fator de produção, cresceu ainda mais em relevância. Evoluíram-se outros fatores de produção, mas a produção também migrou para regiões com oferta hídrica cada vez mais escassa. E por que não citar os desafios trazidos pelas mudanças climáticas globais que têm produzido severos e frequentes períodos de seca em regiões produtoras de cana?

O Mito do consumo de água pela irrigação:

Inicialmente, note que é mais apropriado substituir a palavra consumo pela palavra uso. Consumo traz uma visão equivocada de que a passagem da água no interior da planta faz com que ela se perca de forma permanente, desaparecendo do sistema hídrico: o que está longe de ser verdade.

Uma visão desatenta e não sistêmica pode levar a uma conclusão equivocada de que a cana irrigada, por utilizar água proveniente de rios, represas ou poços, acabe usando mais água que uma cana de sequeiro. Contudo, a cana de sequeiro também precisa de água para sobreviver e produzir. Ela, como qualquer outra planta, além de absorver parte da água da chuva com suas raízes, transporta-a através de passar nos colmos, alcançando as folhas; em seguida, a água é liberada na atmosfera pela transpiração. A cana irrigada é idêntica à de sequeiro, mas, além da água da chuva, também transpira a água que lhe foi entregue pela irrigação no período de seca.

Numa visão mais holística precisamos trazer a eficiência produtiva para o centro da conversa. A cana irrigada, por sofrer menos estresse hídrico e nutricional, tem capacidade de produzir mais colmos com cada gota de água que utiliza. A pesquisa da Embrapa tem mostrado que a cana irrigada, quando comparada à de sequeiro, extrai mais de seu potencial genético e produz até 50% mais colmos e açúcar para a mesma quantidade de água utilizada.

Por exemplo, um canavial de sequeiro que recebeu 1200 mm de chuva e produziu 80 ton/ha obteve uma eficiência de 66 kg/mm. No Cerrado, com a tecnologia que temos hoje, conseguiríamos adicionar 300 mm de irrigação e produzir, na mesma área, 120 toneladas, ou seja, uma eficiência de 80 kg/mm. Ou poderíamos adicionar 450 mm de irrigação aos 1200 mm da chuva e produzir 150 ton/ha, gerando eficiência de 83 kg/mm.

A demanda de cana-de-açúcar não é regida pelo setor sucroenergético, mas pelo mercado consumidor, seu modo de vida e sua demanda por alimento, energia, entre outras coisas. Cabe ao setor sucroenergético responder como produzir essa cana e em que níveis de eficiência e sustentabilidade. Como a cana irrigada usa menos água para produzir cada tonelada de colmos, se o setor sucroenergético resolver que produzirá, 20, 40 ou 60% dessa produção anual em sistema irrigado, no final das contas, a necessidade de água para atender a demanda anual de cana, na verdade, reduzirá.

Para isso, seria fundamental alocar a produção irrigada exclusivamente onde há disponibilidade hídrica - água outorgável. Mas o fato é que as lavouras irrigadas, mesmo utilizando água além da que vem das chuvas, produzem mais e com maior eficiência. E na contabilidade final, a cana irrigada utiliza menos água para produzir a mesma tonelada de colmos ou açúcar.

Produção irrigada, chave para sustentabilidade:

O sistema de produção irrigada de cana-de-açúcar, como qualquer outro, deve obedecer às melhores práticas de sustentabilidade e atender rigorosamente às legislações ambientais. Isso inclui utilizar única e exclusivamente água outorgada. A outorga é concedida com base no estudo do histórico de vazões do manancial, garantindo que a maior fração permanecerá intacta, preservando a vida do ecossistema. Para isso, é crucial uma gestão responsável dos recursos hídricos pelos órgãos públicos e a participação efetiva, cooperativa e harmoniosa dos usuários nos comitês da bacia. Nesse campo, apesar do grande avanço nos últimos anos e da moderna legislação de águas do Brasil, ainda há muita oportunidade de avanço.

Para uma análise técnica e racional da sustentabilidade da produção irrigada de cana-de-açúcar, é fundamental a compreensão dos seguintes fatores:

1) a quantidade de água utilizada por toda agricultura irrigada do País representa menos de 0,6% do que existe em nossos rios;

2) o Brasil possui umas das legislações de água mais modernas do mundo;

3) é possível disponibilizar para produção irrigada de cana, de forma sustentável, uma pequena fração da vazão outorgável ainda disponível em muitas regiões do País, e isso só depende de gestão técnica e responsável, focada na sustentabilidade ambiental;

4) estimativas apontam capacidade de expansão sustentável da produção irrigada no Brasil para, pelo menos, mais 55 milhões de hectares.

5) a produção irrigada pode ser mais eficiente no uso da água do que a produção de sequeiro.

Percebemos, portanto, que a produção irrigada de cana-de-açúcar é uma oportunidade para o Brasil e o setor sucroenergético reduzirem a quantidade de água utilizada hoje para atender a demanda de cana-de-açúcar, de etanol, e de energia elétrica, entre outros.

Ademais, o ganho de eficiência promovido pelo sistema irrigado de produção implica em verticalização da produção, ou seja, maior produção em menor área. Assim, a quantidade de terra necessária para atender a demanda de cana-de-açúcar poderia ser substancialmente reduzida, sobrando terra para ser destinada a outros usos, inclusive para preservação de vegetação nativa.

Vale ainda enfatizar que a biomassa de palha, a produção de raízes e a atividade microbiológica do solo é proporcional ao vigor da produção de biomassa aérea da cana-de-açúcar. Por isso, a cobertura e a proteção do solo, a redução da erosão, a infiltração da água, a redução da compactação, a atividade microbiológica do solo e o sequestro de carbono são proporcionalmente maiores em sistemas irrigados racionalmente conduzidos do que em sistemas de sequeiro.

Por essas razões, sistemas de produção como o da cana irrigada, mais modernos, eficientes, verticalizados e racionalmente conduzidos, podem propiciar maior sustentabilidade ambiental do que a produção de sequeiro.

Maior longevidade do canavial:

O principal fator de redução da produtividade está associado à perda de população de colmos, que é resultado, dentre outros fatores, do pisoteio, abalo e arranquio de soqueira, aumento da infestação de pragas e doenças e de degradação da fertilidade do solo.

A longevidade de um canavial é frequentemente definida por uma produtividade mínima aceitável. Algumas vezes, esse número é definido empiricamente. Em outras, é baseado em alguma métrica financeira. Mas, seja empiricamente, ou através de algum critério financeiro, de forma geral, sempre se define uma faixa de produtividade mínima aceitável. Em uma usina com níveis de produtividade inferior, pode ser um TCH (toneladas de cana por hectare) de 40 ou 50. Já nos melhores canaviais do país, a produtividade mínima aceitável poderia ser um TCH de 80 ou 90. Contudo, todas essas referências se referem a um canavial de sequeiro.

Se fosse mantida essa mesma referência para áreas irrigadas, certamente a longevidade do canavial irrigado aumentaria substancialmente porque levaria mais tempo para um canavial irrigado chegar a esses baixos níveis de produtividade; devido ao fato de ele possuir melhores condições hídricas e nutricionais no momento da rebrota. Portanto, perde população em velocidade menor que o canavial de sequeiro. O canavial irrigado, além de manter maior população de colmos, oferece melhores condições para o crescimento de colmos ao longo do ciclo.

Outra questão importante é que a maior oferta hídrica e o melhor aproveitamento nutricional do canavial irrigado permitem que ele compense as eventuais falhas nas linhas por perda de população. Ou seja, uma falha de um metro na linha de cana irrigada tem menor peso na redução de produtividade do que o mesmo metro em área não irrigada.

Considerando a vida útil dos equipamentos de irrigação, seja de pivô ou gotejamento, é possível conduzir dois ciclos de 8 a 10 anos sem grandes intervenções nesses equipamentos. Mesmo no gotejamento, pode-se optar por trocar apenas as linhas gotejadoras a cada ciclo ou depois de dois ciclos. As linhas laterais (linhas de gotejamento) representam aproximadamente 30% do custo de um sistema novo e, com a troca, poderá operar por mais dois ou três ciclos.

Enfim, comparado a um sistema de sequeiro, é fato que a longevidade do canavial irrigado é maior, atingindo produtividades ao redor de 100-120 ton/ha entre o 12º e 15º corte. Para tais resultados, contudo, não basta adicionar água a um sistema de produção de sequeiro.

A produção irrigada possui dinâmica e práticas bem distintas da de sequeiro. A mera adição de água a um sistema de sequeiro sem ajustes na escolha de variedades, nutrição, tratos fitossanitários, maturação, logística e outros fatores, jamais permitirá extrair o potencial do sistema irrigado. Portanto, um sistema irrigado de produção não se resume à adição de água a um sistema de sequeiro.

Produção verticalizada:

O controle do principal fator de produção – a água – , permite o canavial extrair seu potencial genético e expressar todas as outras melhorias no manejo de excelência. Sem a água, as outras práticas são corroídas e não dificilmente atendem plenamente a expectativa.

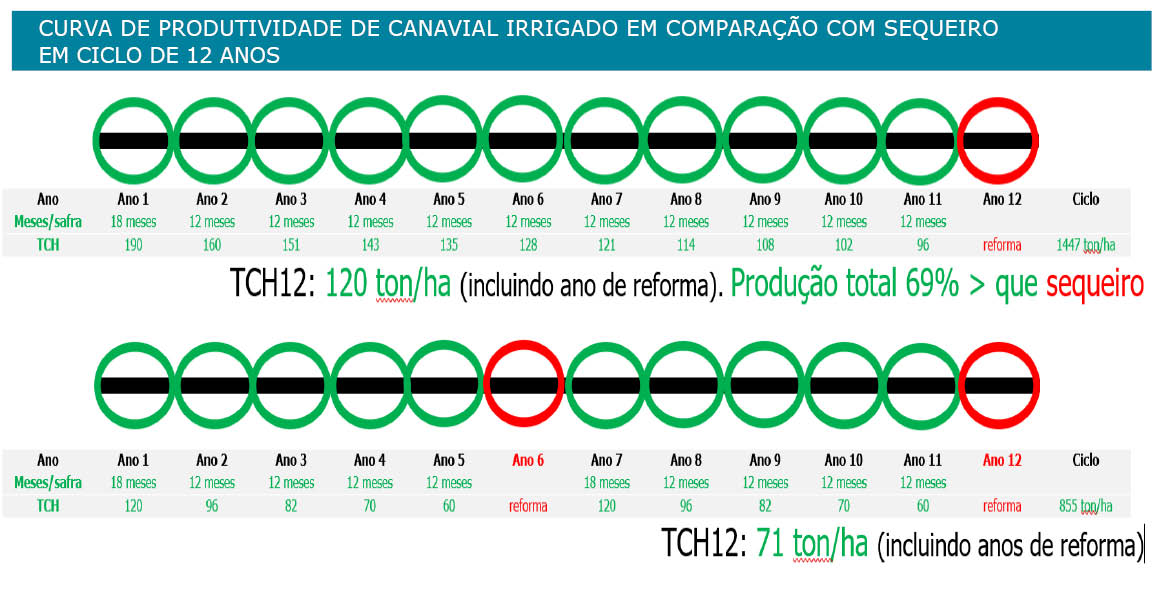

Ao se comparar um ciclo de 12 anos, empregando as recomendações da Embrapa para produção irrigada de cana no Cerrado, com pouco tempo de experiência, as usinas conseguem entregar até 69% mais produção em relação a mesma área em sequeiro.

E como a produção irrigada consegue contornar os problemas dos piores ambientes de solo e da pior janela climática (agosto a setembro), a usina pode adotar a estratégia de alocar sua fração irrigada nos piores ambientes e na pior janela climática, obtendo ainda expressivos ganhos indiretos por direcionar seus melhores ambientes e janela climática para produção de sequeiro.

Por isso, o maior diferencial de adotar o sistema irrigado em uma fração da área da usina não é a produtividade da área irrigada em si, mas a verticalização da produção como um todo, e o ciclo virtuoso que ela traz nas eficiências por tonelada de cana produzida ou moída.

A verticalização da produção reduz a demanda de maquinário e mão de obra por tonelada, reduz a demanda de área e custo de reforma para manter a usina cheia, reduz a demanda por terra, e toda uma sequência de ganhos de eficiência que culminam na redução de custo (CAPEX e OPEX) e demanda de recursos naturais para produzir cada tonelada de cana. Por isso, lastrear parte da área das usinas com sistema irrigado se traduz no ápice da excelência do manejo agrícola, da competitividade e da sustentabilidade do setor sucroenergético brasileiro.