Nicolle Alves Monteiro de Castro

Especialista em Agronegócio da S&P Global Commodity Insights

OpAA80

A filosofia aplicada ao etanol brasileiro

Aristóteles dizia que “devemos tratar igualmente os iguais e desigualmente os desiguais na medida de sua desigualdade”. Será com esta abordagem que governos e consumidores buscarão formas de descarbonizar matrizes energéticas e setores econômicos, garantindo segurança energética e justiça social.

No Brasil, o aristotelismo também é o fundamento base do Artigo 5º da Constituição Federal de 1988, o qual dispõe sobre o princípio constitucional da igualdade perante a lei, entretanto diferentemente da abordagem constitucional o qual trata sobre pessoas. No que tange a este artigo, abordarei os aspectos das igualdades e desigualdades do que até há pouco tempo era visto como uma commodity, ou seja, sem diferenciação sobre seu local de produção ou produtor.

Enquanto o preço do etanol no Brasil e no mundo ainda é majoritariamente orientado pela premissa econômica de oferta e demanda, já é possível afirmar que, perante os compromissos públicos e privados de redução das emissões de GEE – Gases de Efeito Estufa, as políticas públicas dos principais países já ponderam não apenas um prêmio ambiental (financeiro) para o etanol com uma menor intensidade de carbono, como também no caso da Europa, já delimita a origem da matéria-prima.

No Brasil, a política nacional dos biocombustíveis (Renovabio) já exerce o papel de atribuir um prêmio de mercado para os produtores que certificam a sua produção e se tornam elegíveis a gerar CBios no momento da venda do etanol.

Aspectos ambientais: Ao considerarmos que um dos objetivos das políticas públicas de produção e uso de biocombustíveis é o de reduzir as emissões de GEE, a rastreabilidade e elegibilidade das matérias-primas utilizadas para produção dos combustíveis renováveis têm sido temática de discussões globais.

No caso do Brasil, o modelo de contratação da cana-de-açúcar fornecida por terceiros às usinas produtoras de etanol possui usualmente um prazo superior a cinco anos, bem como uma maior concentração de compra com produtores próximos às usinas, facilitando a rastreabilidade e elegibilidade do etanol produzido via cana.

O melhor rastreamento dos fornecedores de cana também possibilita que a indústria incentive, via o compartilhamento de tecnologias e recursos financeiros, uma produção de matéria-prima com menor intensidade de carbono, impactando diretamente no volume total de etanol elegível e na nota de eficiência energética, portanto na quantidade de CBios gerados por litros vendidos.

Em oposto, as plantas de etanol de milho possuem uma maior dificuldade em mapear as emissões atribuídas à produção da matéria-prima, uma vez que existe uma maior pulverização no número de produtores envolvidos na cadeia de suprimentos e, também, uma maior distância das plantas de processamento.

Para efeitos de comparação, de acordo com os dados publicados pelo Observatório da Cana, do total de etanol hidratado produzido no estado de São Paulo, 91,99% é elegível ao programa e possui uma intensidade de carbono média de 27,7gCO2eq/MJ, ao passo que no Mato Grosso, estado que lidera a produção de etanol de milho com 11 plantas em funcionamento, sendo seis exclusivas de etanol de milho e cereais, estes números são de respectivamente 55% e 32,5gCO2eq/MJ. Ainda como efeito de exemplo, de todo o hidratado produzido por uma das principais produtoras de etanol de milho do Mato Grosso, apenas 24% é elegível ao programa Renovabio, com uma intensidade de carbono de 42,9gCO2eq/MJ.

Visando reduzir as emissões totais atribuídas ao processo de produção, alguns produtores de etanol de milho no Brasil e nos Estados Unidos já investem em projetos de CCS, captura e armazenamento de carbono, o qual no Brasil está sendo discutido no PL 1425/2022.

Os fatos acima destacam que, embora os etanóis provenientes do milho e da cana possuam uma mesma característica de molécula, para alguns mercados dispostos a pagar um prêmio para biocombustíveis com uma menor emissão de GEE durante toda a análise de ciclo de vida, o etanol de cana tenderá a gerar um maior valor de mercado.

Garantia de abastecimento via renováveis: O mercado brasileiro de combustíveis possui um grande diferencial perante o resto do mundo, com atualmente 85% da frota de veículos leves como flex fuel. Isso permite que o consumidor exerça um papel fundamental na curva de demanda do etanol, sendo tal decisão de consumo ainda amplamente pautada na diferença entre o preço da gasolina C, a qual possui 27% de etanol anidro, e do etanol hidratado, ou E100.

Este fato nos leva a pensar sobre dois aspectos: a relevância da política de preço da gasolina e o apetite do consumidor brasileiro em pagar um prêmio para abastecer com um combustível de menor impacto ambiental. É sabido (por poucos) que a agenda de descarbonização vai muito além de uma pauta exclusivamente ambiental, porém menor ainda é o número de pessoas que podem financeiramente optar por produtos com uma menor intensidade de carbono, ou seja, que gerem um menor impacto ao meio ambiente.

Ao analisarmos o volume total de etanol vendido pelos produtores brasileiros em 2019, era possível notar a alta dependência da produção originada no estado de São Paulo, a qual correspondia a 43,7% (14,2 bilhões de litros) do total nacional, sendo o estado majoritariamente dependente de cana-de-açúcar. Neste mesmo ano, a participação do estado do Mato Grosso do Sul era de 7,4% (2,4 bilhões de litros), Goiás tinha 3% (977 milhões de litros) e Mato Grosso abarcava apenas 2,1% (696 milhões de litros).

Neste cenário de centralização regional da oferta de etanol, os estados do Sudeste, mesmo com a sua demanda total de combustíveis de Ciclo Otto representando quase 50% da demanda nacional, eram beneficiados com preços de etanol mais competitivos do que as regiões Norte, Nordeste e Sul.

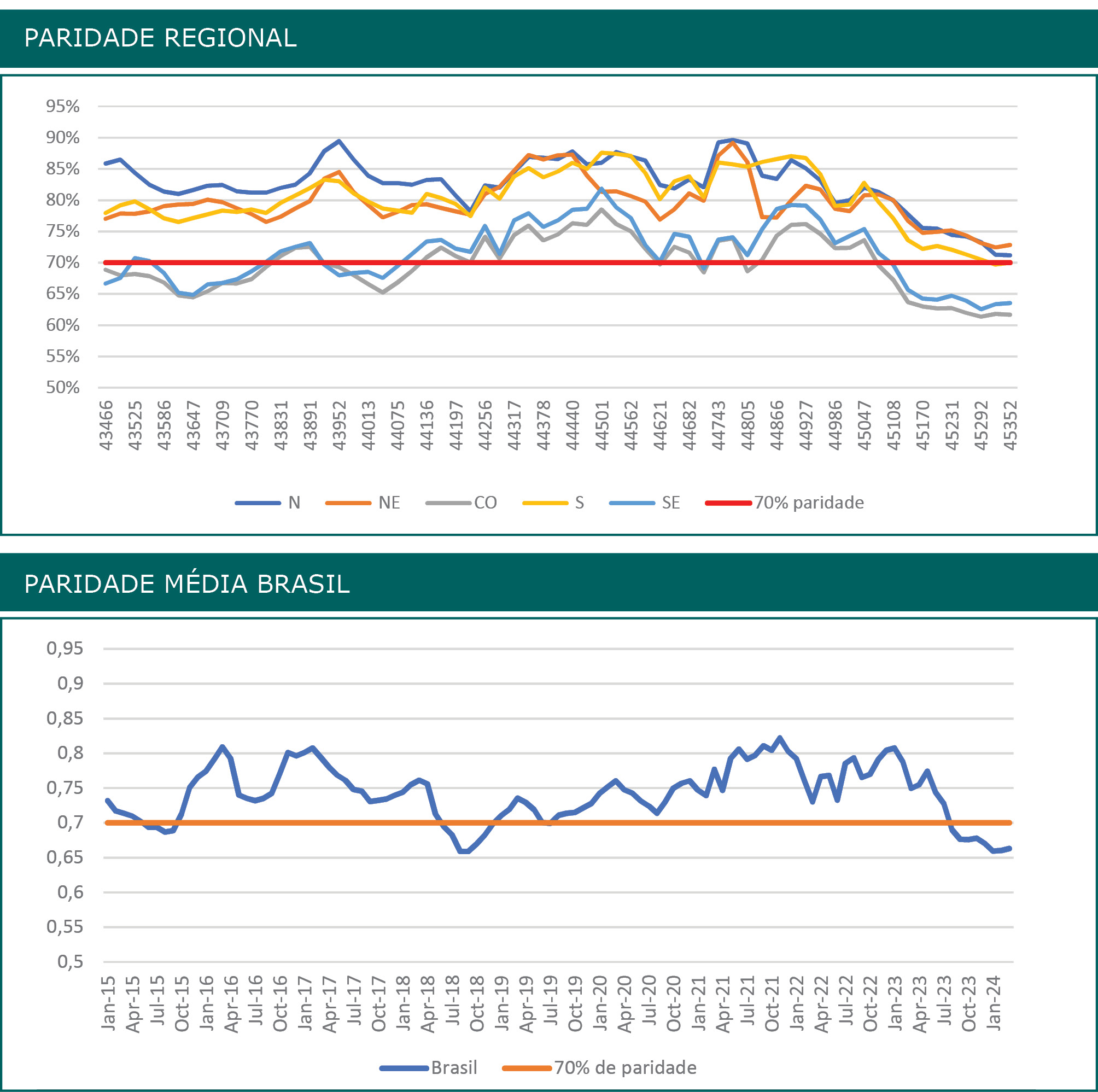

No período analisado entre 2019 e 2023, a paridade do Centro-Oeste se demonstrou mais favorável ao etanol do que nos estados do Sudeste. Entretanto, a demanda total do Ciclo Otto na região foi em média equivalente a 10% da demanda nacional. Observe na próxima página o gráfico de Paridade Regional. Pulamos para 2023, e a expansão da indústria de etanol de milho, majoritariamente baseada entre os estados do Centro-Oeste, já gerou um deslocamento da curva regional de oferta e demanda.

Do volume total de etanol vendido pelos produtores em 2023, a originação no estado de Mato Grosso representou 15,7% (4,5 bilhões de litros); Goiás, 15,2% (4,3 bilhões de litros); e Mato Grosso do Sul, 11,5% (3,3 bilhões de litros). São Paulo, por sua vez, reduziu a proporção para 34,2% (9,8 bilhões de litros).

Com o cenário de oferta regionalmente descentralizado e com um menor efeito sazonal de disponibilidade de produto, a cadeia do etanol de milho favoreceu um novo cenário de paridades positivas ao etanol hidratado nas regiões Sul, Norte e Nordeste, como demonstrado no citado gráfico. A maior oferta de etanol de milho já se demonstrou eficiente para aumentar nacionalmente a atratividade econômica do biocombustível.

O gráfico com a Paridade Média Brasil, na página seguinte, demonstra a paridade nacional média entre etanol hidratado e gasolina no período entre janeiro de 2015 e março de 2024. Ao longo desses quase nove anos, o etanol hidratado ofereceu uma vantagem financeira mais competitiva perante a gasolina entre junho e novembro de 2018, pico da safra de cana-de-açúcar no Centro-Sul do Brasil.

De fato, o advento do etanol de milho proporciou aos consumidores nacionais uma oferta regular, ou seja, sem os efeitos de sazonalidade de preços, novos alcances geográficos de abastecimento de um combustível renovável e a oportunidade de mais consumidores terem a percepção dos benefícios atribuídos ao uso do etanol.

Com base nessas premissas, é possível concluir que o aumento da oferta total de etanol, seja de cana-de-açúcar ou de milho, tenderá a favorecer a sociedade por múltiplas vias:

ampliação da disponibilidade de biocombustíveis no país, preços potencialmente mais competitivos perante o substituto direto fóssil, redução das curvas de sazonalidades de preço, menor exposição aos preços globais de açúcar, geração de uma nova cadeia de valor ao produtor agrícola e, por fim, mas não menos importante, redução das emissões totais de GEEs do setor de transportes do Brasil.

Resolver problemas climáticos e ambientais, ponderando os aspectos sociais e de justiça energética, demandará uma soma de tecnologias e matérias-primas. Logo concluo dizendo: não é sobre o milho versus a cana-de-açúcar, mas sim sobre usufruir do melhor que as opções podem entregar.